January 20, 2025

GREAT FIGURES WHO HAD FAITH IN NICHIREN SHU (1)

By Rev. Sensho Komukai

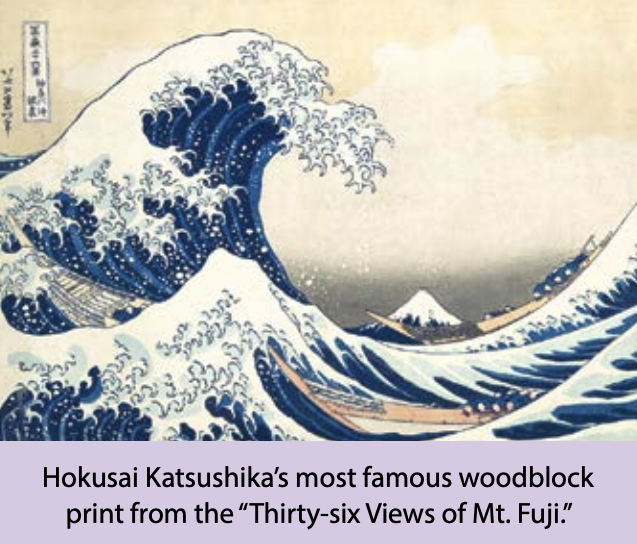

Hokusai Katsushika (1760-1849), born in Tokyo, was an ukiyo-e artist known for his colored woodblock prints. His major works include the “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji” and “Hokusai’s Sketches.” Yet it is little known that he had deep faith in the teachings of Nichiren Shonin and the Lotus Sutra. He especially revered Myoken Bodhisattva (the Deity of the Big Dipper). He often visited Ikegami Honmonji Temple and Horinouchi Myohoji Temple. Whenever he walked outside, he would chant the dharani (spells) of Universal-Sage Bodhisattva. He was so focused on this that he often did not even see friends as they passed by. The dharani of Universal-Sage Bodhisattva begins with “Atandai, tandahatai, tandahatei….” According to Chapter 28 of the Lotus Sutra, anyone who hears this dharani will be protected by the Universal-Sage Bodhisattva and be able to ward off evil spirits.

In Hokusai’s name, “Hoku” means “North.” He took this name due to his wish for long life, because it was believed in China that human life would be determined by the Big Dipper in the North. “Sai” means “to shut yourself away in your home on an unlucky day and to prohibit anyone from entering the house.” Therefore, the name Hokusai came from his sincere wish to be protected by the Deity of the Big Dipper. To avoid any evil influences, he chanted the dharani whenever he had to go out.

Despite his devout faith, he created few works that were overtly religious. This is because ukiyo-e art was closely related to worldly affairs. Religious subjects were not considered suitable themes for ukiyo-e paintings. One of his few works dealing with his religious background is An Illustration of the Responsive Manifestation of the Great Goddess Shichimen, which shows how frightened people were to see a female dragon with seven faces, while Nichiren Shonin calmly chanted the sutra before her. This picture was completed two years before Hokusai passed away.

Hokusai preferred a modest life and simple food, not caring about his appearance. An apprentice at a bookstore who went in and out of Hokusai’s house on errands said, “Hokusai would make a rough sketch, shutting himself up in a six-mat tatami room with little sunlight. A futon was left spread out near his working table and a rice bowl or a pot that looked as if they had never been washed were on the floor. All his clothes were begrimed with dirt and entirely worn out.” He showed no interest in anything but the development of his art. He devoted himself intensely to the pursuit of a perfect piece. Just before he died, he said, “If I were given ten more years of life, or say at least five years, I would be able to become a genuine painter with absolute value.” He died at the age of 90.